Guest Post: Navigating the Ethical Paradox: Including Young Children’s Voices Without Tokenism

Posted 29th April 2025

Lauren Henderson, PhD researcher from Swansea University, reflects upon the ethical considerations present when carrying out research with very young children. This is related to her reflections during her current PhD research which is interested in exploring young children’s (aged 0-5) participation rights within Early Education and Care settings in Wales.

*The following guest post represents the author’s personal view and does not necessarily represent the view of EECERA as a whole. Any issues or questions arising from the content of this post should, therefore, be directed to the author and not EECERA.

Interested in writing a guest post for the EECERA blog? Visit the Write for Us page for more info.

Imagine walking into a busy nursery or other early years setting, where children are constantly communicating their ideas, feelings and preferences, through a vast array of ‘languages’ (Edwards, Gandini, and Forman 2011). Even the littlest ones—those who barely form words—communicate through smiles, gestures, cries and bursts of laughter. As researchers, we’re increasingly convinced that these early expressions hold vital clues to understanding children’s experiences. In relation to my current PhD research which explores young children’s experiences of their participation rights within early years settings, considering the multitude of ways infants and toddlers may be sharing their perspectives is of significant interest. Yet, a persistent ethical conundrum shadows these efforts: How can we ensure that very young children, with their unique developmental understanding of their worlds, are not merely included as tokens in research, but are truly heard on their own terms?

In today’s post, I intend to reflect upon this ethical paradox, blending academic insight with relevant highlights from my ongoing research with young children. The goal is to explore how researchers can authentically include young children’s voices while steering clear of the pitfalls of tokenism—despite the challenges posed by their developmental cognitive understandings and different modes of communication.

The Promise and Challenge of Participatory Research

The move towards participatory research reflects a growing recognition of children’s rights and a shift away from studying children as passive subjects (Angelöw and Psouni 2025). Instead, we now strive to invite them into the conversation about their own lives.

Yet, working with infants and toddlers is anything but straightforward. Picture a research session where an infant or young toddler is given the opportunity to “answer” questions through play. Their responses might be a delighted squeal or a curious gesture, leaving us wondering: Is that a genuine expression of their experience or simply a fleeting reaction to something novel in their environment?

These challenges remind us that the very nature of early childhood communication is different to our own methods. Unlike older children or adults, toddlers do not articulate thoughts in structured sentences. Their “answers” might come in the form of a choice of toys, a burst of energy during play, or even a momentary disengagement. The challenge lies in interpreting these expressions without overlaying them with adult assumptions.

The Ethical Paradox: Authentic Inclusion or Tokenism?

Herein lies the dilemma. On one hand, the inclusion of young children in research is a powerful affirmation of their right to be heard. I consider this to be an important aspect of my own research methodology and approach, particularly as I am actively exploring young children’s experiences of their participation rights, a core aspect of which relates to having their voices and views heard and considered in decision-making processes that affect them. Therefore, it seems completely hypocritical and unethical not to purposely engage with listening to children’s voices. However, in actively seeking involvement from young children during the research process, I fear that the risks of tokenism loom large and often find myself feeling caught between the desire to include the voices of the youngest participants, and the worry that their contributions might be misinterpreted or merely symbolic. In such moments, the risk is that adult meanings are inadvertently projected onto children’s actions, thereby unintentionally diminishing the child’s authentic perspective.

This tension is not just methodological; it’s deeply ethical. It calls on us as researchers to ask: Are we capturing the true essence of a child’s voice, or are we merely ticking boxes in our pursuit of inclusivity? It forces us to remain reflexive and continually question our interpretations to consider if we are truly listening to the child’s voice, or if we are filling in the gaps with our own adult-centric assumptions.

In reflecting on the process of engaging very young children through child-friendly research methods, I have become increasingly aware of the inherent challenges in capturing the true depth of their perspectives. Although these young participants readily accept invitations to join in with play-based data gathering activities, their responses often do not extend to a full acknowledgment of the underlying research agenda. This gap raises important questions about the nature of their participation—namely, whether what appears to be inclusion is, in fact, tokenistic.

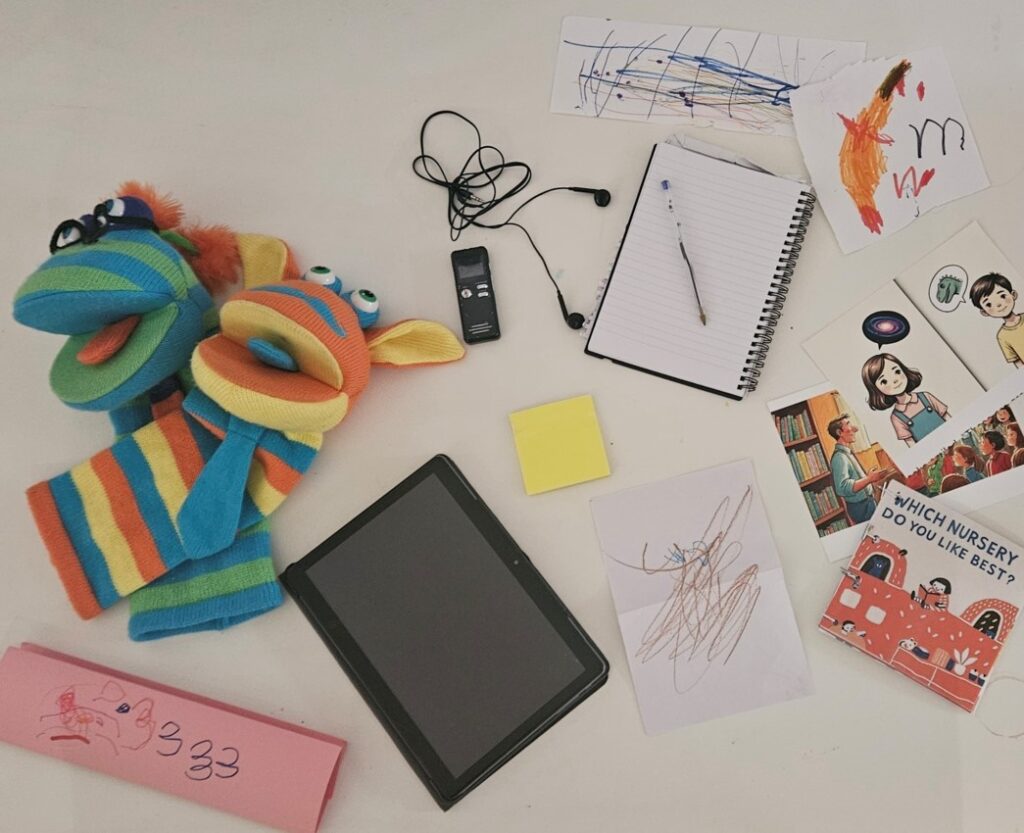

On one level, the child-friendly design of the methods used within my current research project succeeds in providing an accessible entry point into the research process. Young children are encouraged to express themselves through play, drawing, or simple verbal interactions, which can be seen as affirming their agency. Yet, given their developmental stage, these responses may lack the complexity or critical engagement required to grapple with abstract research concepts. In this sense, their participation might be interpreted as symbolic rather than substantive—an ethical compromise where inclusion does not equate to active, informed contribution.

These challenges underscore the importance of adhering to robust ethical frameworks that recognise the complexities of engaging young children’s voices authentically. The newly revised EECERA Ethical Code for Early Childhood Researchers (Bertram et al. 2025) emphasises principles of respect, democratic values, and safeguarding children’s rights in research, providing timely guidance for navigating such ethical tensions.

The Value of ‘Tokenistic’ Participation and the Value of Participation Beyond Research Objectives

However, I have also come to appreciate that perhaps even tokenistic participation may hold significant value. By inviting young children to take part, researchers are compelled to consider their viewpoints, however preliminary these might be, rather than dismissing them outright. This inclusion disrupts a more pervasive pattern of active exclusion, where the voices of those with limited communicative abilities might otherwise be ignored entirely. Even if the children’s contributions do not fully engage with the research agenda, their involvement signals a commitment to recognising and respecting their presence as stakeholders in the research process.

Ultimately, while the current practice may sometimes be limited to tokenistic inclusion, it represents a crucial step forward. It demonstrates a commitment to inclusivity and underscores the ethical responsibility to listen to even the youngest members of our communities (Lundy 2018).

Let’s take a step back. What if we looked at participation not as a means to an end (i.e., answering our research questions) but as an end in itself—a genuine process of giving young children space to be themselves?

Traditional research methods often expect neatly aligned responses that match predefined questions. However, for infants and toddlers, participation might mean something entirely different. By redefining what counts as “participation”, we open up a richer, more inclusive understanding of children’s agentic behaviours. As has been done in previous research specifically focused on listening to young children’s voices (for example, (Blaisdell et al. 2018), instead of forcing children to fit our heuristics, we should adapt in order to capture the fluid, dynamic, and multi-faceted ways they express themselves. In doing so, we recognise that a child’s spontaneous play or non-verbal cues are valid forms of communication—ones that reveal their preferences, feelings, and unique perspectives of their lived experiences.

Final Thoughts

The journey toward an authentic inclusion of young children’s voices in research is filled with uncertainties and challenges. There’s no simple answer to the ethical paradox we face—balancing the need for genuine participation with the risk of tokenism is an ongoing process.

What remains clear is that the ethical challenge is not solely about whether we include young children, but how we include them. By adapting methodologies to honour the unique ways in which infants and toddlers communicate, we move closer to a research practice that is both respectful and truly inclusive.

In the end, our task is to reshape our research spaces so they fit into children’s worlds—not the other way around. In doing so, we not only give young voices the space they deserve but also enrich our understanding of the vibrant, multifaceted ways that children experience and interact with the world around them.

References

Angelöw, Amanda, and Elia Psouni. 2025. “Participatory Research with Children: From Child-Rights Based Principles to Practical Guidelines for Meaningful and Ethical Participation.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 24 (January). https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069251315391.

Bertram, Tony, Chris Pascal, Helen Lyndon, Julia Formosinho, Donna Gaywood, Colette Gray, Jennifer Koutoulas, Eleni Loizou, Michel Vandenbroek, and Margy Whalley. 2025. “EECERA Ethical Code for Early Childhood Researchers.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 33 (1): 4–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293x.2024.2445361.

Blaisdell, Caralyn, Lorna Arnott, Kate Wall, and Carol Robinson. 2018. “Look Who’s Talking: Using Creative, Playful Arts-Based Methods in Research with Young Children.” Journal of Early Childhood Research 17 (1): 14–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718×18808816.

Edwards, Carolyn P, Lella Gandini, and George E Forman. 2011. The Hundred Languages of Children: The Reggio Emilia Experience in Transformation. 3rd ed. Santa Barbara (California); Oxford (England): Praeger, Cop.

Lundy, Laura. 2018. “In Defence of Tokenism? Implementing Children’s Right to Participate in Collective Decision-Making.” Childhood 25 (3): 340–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568218777292.

About the Author

Lauren Henderson is a PhD researcher at Swansea University. Focusing on young children’s (aged 0 to 5) participation rights in pedagogical practice within early childhood education and care (ECEC) settings in Wales. Her research explores how children’s voices are recognised and used to implement decision making processes during everyday practice within nursery settings. Prior to beginning her doctoral studies, Lauren worked as a primary school teacher for over 10 years across England and Wales, where she developed a strong interest in children’s rights and inclusive pedagogies.

LinkedIn profile: https://www.linkedin.com/in/lauren-henderson-b8b115b4/