EECERA Conference 2025 – Guest Blog # 45: Beyond Inclusion

Posted 25th August 2025

One of a series of short blog posts by presenters who will be sharing their work at the upcoming annual conference in Bratislava, Slovakia. Any views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official stance of their affiliated institution or EECERA.

Beyond Inclusion: How Early Childhood Education Sustains Whiteness

By Duha Ceylan

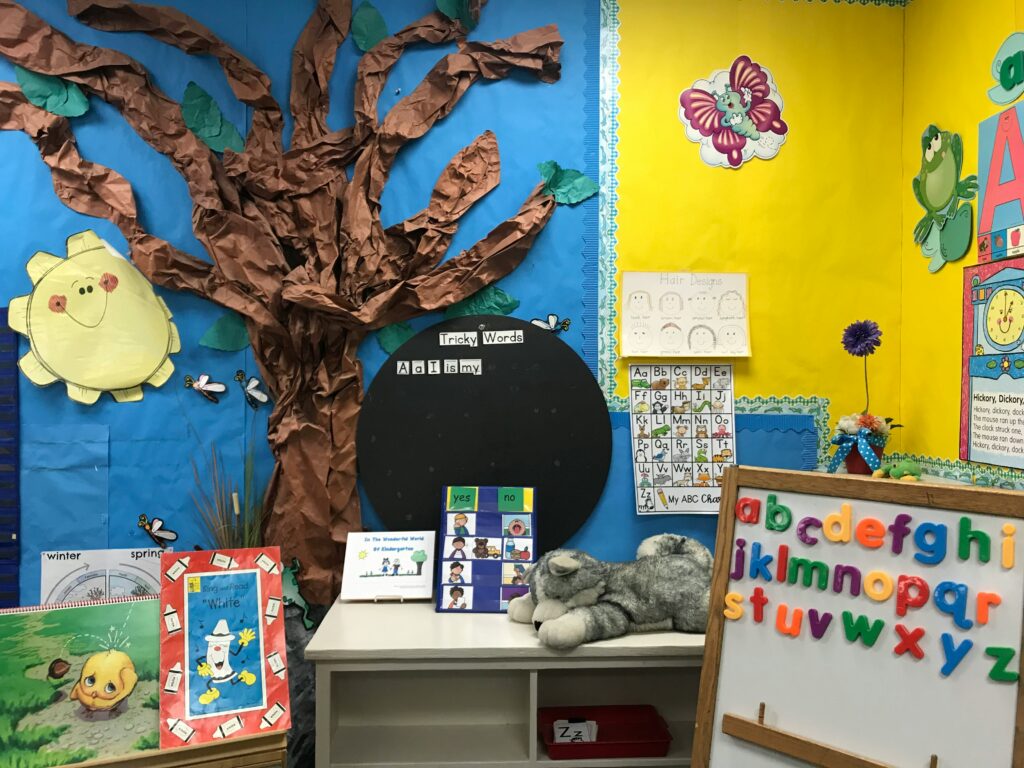

Photo by Monica Sedra on Unsplash

Across Europe, early childhood education and care (ECEC) is celebrated as a space of inclusion and opportunity. Governments and institutions present kindergartens and childcare centres as neutral, benevolent places where children are given the “best start in life.” However, my research with Syrian mothers in Belgium, Germany, and the Netherlands reveals a more troubling reality. Behind colourful classrooms and smiling posters, ECEC operates as a system of racial governance, sustaining whiteness under the guise of care.

White childhoods as the invisible norm

In this work, I introduce the concept of white childhoods: a framework describing how dominant ideas of childhood are shaped by Western, middle-class, white, heterosexual, and non-disabled norms. These ideals are treated as universal, yet they determine which children are seen as innocent, worthy of investment, and “properly developing.” Children who do not fit this mould, migrant, racialised, disabled, or nonconforming, are judged against it and often found lacking.

This structuring force is not accidental. It is rooted in colonial histories where education was used to discipline racialised children, stripping them of language, culture, and family ties. Today, those legacies persist. Families are told that to belong, they must perform childhood and motherhood in ways recognisable to the state.

Everyday erasures: language, emotions, and surveillance

The mothers I interviewed described pressures to abandon their home languages. One was told, “Speak only German at home; Arabic will confuse your child.” This message, repeated across institutions, frames Arabic, Kurdish, or Turkish as threats to development, despite decades of research showing the benefits of bilingualism. What Blommaert (2010) calls linguistic gatekeeping ensures that only specific languages count as valuable, typically those tied to whiteness and national identity.

Emotional expression was also policed. A child described as “too quiet” or “not smiling enough” was flagged as a problem, with suspicion extending to the mother. Teachers encouraged parents to “show more warmth” or “model confidence.” Such advice sounds supportive but enforces a narrow emotional ideal: cheerful, transparent, and always legible. As Sara Ahmed (2012) reminds us, emotions are political. Here, they become tools to discipline children and mothers into white, middle-class norms.

Surveillance extended to mothers themselves. Their parenting, home practices, and even employment status were closely monitored. Access to childcare was often tied to job readiness, pushing women into labour markets while simultaneously scrutinising their caregiving. As one mother put it: “They think we do not try hard enough. If the child does not speak well, the mother did not do enough.” Care, in this system, is conditional, not a right, but a contract.

Refusal and imagining otherwise

Mothers and children did not only comply. They also refused. Some insisted on speaking Arabic at home despite institutional pressure. Children resisted expectations by being loud, withholding smiles, or rejecting touch from teachers. These refusals disrupted the fiction of neutral care. They showed that belonging, when tied to whiteness, comes at too high a cost.

Building on abolitionist and decolonial theories (Wynter, 2003; Love, 2019), I argue that inclusion cannot be the solution. Diversity and inclusion initiatives often reproduce the same structures they claim to fix, absorbing critique while keeping whiteness at the centre. Instead, we need to ask: What if early education was not designed to integrate families into the nation-state, but to sustain collective care outside of it?

Through speculative interviews, I worked with mothers to imagine alternatives. In these visions, care is communal, not surveilled. Children learn through multilingual play, not correction. Mothers share responsibility without being judged against nuclear family ideals. In one vignette, a mother drops her child at a space filled with Arabic books and Kurdish songs, greeted by caregivers who know her by name, not by case file; no paperwork, no suspicion, care.

Beyond reform, toward abolition

This research suggests that ECEC, as currently structured, cannot be reformed to serve racialised families. Inclusion only deepens the demand to conform to white childhoods. Abolition, by contrast, asks us to dismantle these foundations and reimagine education beyond state whiteness. Rather than asking how migrant children can “catch up,” we should ask what becomes possible when no one has to prove their right to belong. What futures open when care is not conditional, when languages are celebrated equally, and when children are not disciplined into emotional and behavioural conformity?

These are not distant utopias. They are already being practised in fragments, when mothers refuse to give up their languages, when children resist institutional expectations, and when families care for each other beyond state oversight. Paying attention to these refusals reveals that the future of childhood is not something we must wait for. It is something already being built.

References:

Ahmed, S. (2012). On being included: Racism and diversity in institutional life. Duke University Press.

Blommaert, J. (2010). The sociolinguistics of globalization. Cambridge University Press.

Love, B. L. (2019). We want to do more than survive: Abolitionist teaching and the pursuit of educational freedom. Beacon Press.

Wynter, S. (2003). Unsettling the coloniality of being/power/truth/freedom: Towards the human, after Man, its overrepresentation—An argument. CR: The New Centennial Review, 3(3), 257–337.

Duha Ceylan will present work referred to in this blog in Symposium Set B20 | Tuesday 26th August 2025 (Schedule liable to change; please refer to final programme for details).